Pessimism is the tendency towards negative thinking and to focus on negative outcomes. When we are pessimistic we are inclined to see the detrimental aspect of a situation, a person, or an event.

Pessimism, sadness, or other negative states can be useful in specific situations and in moderation. However, constant exposure can have harmful long-term impacts not only on our mental health but have physical consequences too.

Our current society seems to focus much on the bleak aspects of life, like the daily news, most of the dominate headlines trends towards the negative. The environment we live can unconsciously play a role in determining our collective outlook. According to the World Economic Forum, the majority of people across 38 countries around the globe, have an overly pessimistic view. Respondents were asked about terror attacks, the murder rates, foreign prisoners, etc. and the majority of respondents overestimated the figures in the country they were in. How did we collectively get so pessimistic?

Origins of Pessimism

There are a few reasons we are prone to think from a negative perspective:

Primitive/Ancestral Past

Pessimism can be rooted in our primitive past. We needed to always be alert for dangers that surrounded us and on the lookout for the worst that could happen to be able to navigate around it. We were in survival mode and had to be ready for the snowstorm, the torrential rainfall, attacks from predators, disease, and the untimely death of our close community member.

Brain Theory

If we look into the brain, neuroscientist Paul MacLean formulated the Triune Brain Theory (the 1960s), which divides the human brain into three distinct regions. Although recent evidence has shown several regions of the brain are involved in the primal, emotional and rational mental activities. Nevertheless, MacLean’s model provides an easy-to-understand approach referring to the hierarchy of brain functions.

- The Reptilian or Primal Brain: Is responsible for our primitive drives (procreation, self-preservation, survival), reflexive behaviours (muscle control, fight, flight, freeze response) and procedural memory (riding a bike).

- The Paleomammalian or Emotional Brain: It area contains emotion memory and processing (sadness, happiness, pleasure, etc), and attachments such as parenting.

- The Neomammalian or Rational Brain: This part controls high order processes such as language, emotional regulation, reasoning, self-control and planning.

The Reptilian Brain (Primitive or Lizard Brain) keeps us safe, as it did our early ancestors. A healthy and functioning Reptilian region is largely responsible for detecting and responding to immediate threats within our environment, like getting out of the way of a vehicle barreling towards us. We don’t have time to think about it we just instantly act.

The Paleomammalian Brain (Emotional Brain) evaluates everything as either pleasurable or distressing, and seeks to repeat pleasure and avoid pain. This area does not apply logic.

We might not be living in the same primitive world, but we have the potential to meet situations which are viewed as potentially threatening and dangerous. Our current world is more emotionally taxing than physically dangerous, however, our brains do not know the difference that we are not actually at physical risk. If we emotionally sense that someone or something is a threat to our well-being, our Paleomammalian Brain evaluates this and will trigger the Reptilian Brain to respond to adverse emotional situations in a fight, flight and freeze fashion.

Being pessimistic puts our defences on alert, ready and prepared for the worst can keep us alive. According to the book Tame the Primitive Brain, the primitive brain hates chaos and unpredictability and defaulting to the negative is the best survival strategy. The comfort zone of this area is the worst-case scenario.

Our Reptilian and Paleomammalian Brains work together — ready to respond to any foreseen threats. When we view the world through these brains we are in survival and fear-based modes of reacting.

The Neomammalian or Rational Brain, specifically the prefrontal cortex does not fully develop until we are in our mid-20s. This region is responsible for functions like reasoning, impulse control, and predicting long-term consequences. Trauma has a possibility to delay to stunt the development of the Rational Brain as well as increase activity in certain areas of the Reptilian and Paleomammalian Brains.

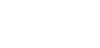

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Psychologist Abraham Maslow (1943) introduced the Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory which reflects our universal needs and describes the stages of emotional growth.

When a need (Basic, Psychological, or Self-Fulfillment need) has mostly been satisfied, then we naturally direct our focus towards meeting the next set of needs that we have yet to meet.

Many of us teeter between having our Basic needs and Psychological needs met, specifically our Safety needs (personal security and resources), Love and Belonging, and Self-Esteem. Many of us tend to get stuck in these lower to middle ranks of Maslow’s hierarchy.

Our media and mass marketing globally play a big role in telling us we are not enough unless we have this, look like that, or be this way. It’s no surprise many of us get stuck, and when those needs can never be fulfilled based upon society’s standards, it’s natural to develop a pessimistic view of our world and our lives.

Nurture (Inner Child)

Another explanation for a pessimistic outlook can also be traced back to our childhood. When we grow up in a home where our emotional needs were not

consistently validated or adequately responded to, we link our parent’s inability to acknowledge our emotional needs and us not being worthy of love. To avoid further feelings of disappointment and discouragement, we develop a pessimistic perspective.

The late John Bradshaw popularized the term “inner child,” and wrote several books on the topic. Every single one of us has an inner child, it represents our child-like qualities of wonder, awe, excitement, playfulness, joy, sensitivity, authenticity, and innocence. A nurtured, acknowledged, understood and listened to “inner child” can cultivate such peace and beauty in this world.

On the flip side, if our child has been wounded, and many of our inner children have been; our inner child can play out our accumulated pains and fears and our propensity to have a bleak outlook on life and situations which surround us. A wounded inner child wreaks havoc in our relationships, our sense of belonging, our feelings of safety, the interaction we have with the others and our world view.

Nature (Temperament: Dandelion vs. Orchid)

The book, The Orchid and the Dandelion: Why Sensitive People Struggle and How All Can Thrive written by W. Thomas Boyce M.D, argues that children are not equally susceptible to trauma.

Approximately 4 of 5 children tend to show a biological indifference to adversity and stress. This also is dependant on the severity of the situation. However, these children can generally thrive in the majority of environments, similar to the flowering plant — dandelions.

About 1 of 5 children show an immense susceptibility to both negative and positive environments. When raised in a supportive and nurturing environment, this minority of children tend to excel. The opposite is true when raised in adverse and stressful social conditions, they exhibit greater distress and illness. This is similar to orchids, which need a particular environment to thrive, but when they do thrive their flowers are delicate and uniquely beautiful.

For some of us, pessimism can be a natural disposition and for others, it can be environmental factors which contributed to how we view the world.

What can be done?

Since we live in a society that prioritizes consumerism over internal wholeness, reports daily on negative occurrences, combined with primal ancestry, our childhood experiences, and nature susceptibility — it’s no surprise that many of us are prone to pessimism.

As children, we may not have been able to control our environments or aware of our highly sensitive nature. Not knowing that some of us are naturally more responsive to our circumstances.

As adults, we can educate ourselves and choose circumstances we surround ourselves in. With the right kind of knowledge and self-nurturance, we can reprogram our conditioned responses or replenish what we did not receive in childhood. Our brains have been proven to be neuroplastic and can change throughout life. We can change how we feel from a fear-based response to an optimistic outlook.